If you type “Ronald Alan Milbourn” into a search-engine, chances are none of the faces you’ll find staring back at you will be my poppa.

Ronald Alan Milbourn (1913-1988)

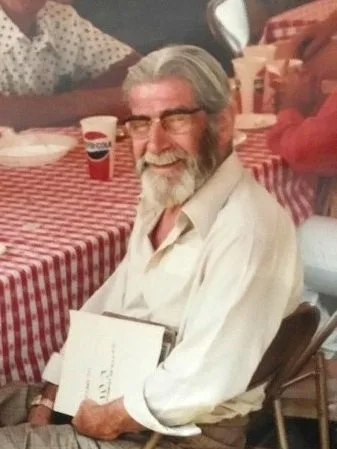

Here is the Paterfamilias enjoying a cheeseburger on the “Natches” paddle-steamer, moored on the Mississippi in Saint Louis, summer of ’85.

And it may well be the only digital image you’ll ever find of him, apart from here on the Milbourn family tree.

Which kind of makes my point for me —

Pops was not an Internet super-star.

You’ll find no pages covering his war exploits. Nothing about his success in business. Not even a mention of him being a good husband, or a kind and loving father.

Nothing.

Until now, that is…

“The war years“

1941-1945

To be honest, I simply don’t know much about what Pater got up to during the war. His generation didn’t discuss their war experiences with you — unless you’d been there too — but certainly not with curious little boys.

I regret now I didn’t quiz him on it when I grew older, but what I do know, is this.

The Royal Artillery

Pops joined the Royal Artillery in 1938, was seconded into the Rough Riders, and in 1940, followed by 4 weeks of “sub-zero” training and cooperation with the Canadian Army in Petawawa, Ontario (messing about in the snow, he called it).

In 1941 “2nd Lieutenant Milbourn” freshly qualified as a Bofors gunner (see picture above), was then assigned to protect the ships on two convoys to and from the USA and Canada.

Pops didn’t like to talk about it, but he did tell me once, the convoys were attacked almost nightly, by German U-boats, aircraft, and warships; many were sunk.

In the 2nd World War, these Arctic Convoys were the way some very brave men (my father among them), faced down the Nazis.

These men were heroes.

“After the war“

Honesty is the best policy

Jobs were hard to find, and for a while young Ronald Alan Milbourn tried his hand at selling advertising space, for what was an important journal before the war — “The African World”.

Unfortunately, their distribution numbers were slipping, but pops had been instructed to tell any potential advertiser they were growing; which, of course, he knew to be false. As someone who couldn’t, or wouldn’t tell a lie, this didn’t set well with the Paterfamilias. It didn’t set well at all.

One day, next on the call sheet was a large potential advertiser. A Lord of the Realm, no less. So, he was definitely someone who would have to be told the truth. At the meeting, young Ronald must have handled that part of the sales pitch with quite some sensitivity, or what transpired next would never have happened.

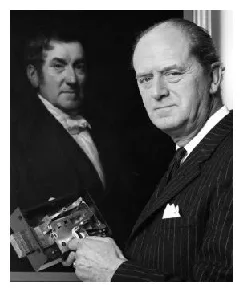

George Charles Hayter Chubb

The then Lord Hayter, offered my father a job as his new “Chubb Lock & Safe City Manager” ― “city” being the City of London. I don’t know, but I can only imagine his Lordship saw a man of integrity, and valued his honesty.

This wasn’t some cushy desk job, by the way. As Chubb Lock & Safe’s City Manager he needed to hold meetings with The Bank of England, all the International Banks in the City, and many other clients in London, then manage design staff, and production, in Wolverhampton.

During the 60s and 70s, these strongrooms and vaults were the high-value targets for bank robbers and safe crackers, and it took a lot of hard work and expertise, to stay one step ahead.

Over a 25-year career, he planned, built, and installed some of the highest value safes, strongrooms, and vaults for the Bank of England, and all the foreign National Banks in the financial district of the City of London, called the “Square Mile”.

He did so well with managing the new City office for Chubb, in 1948 he was appointed General Manager for Scotland and tasked with opening this new territory.

I have many happy memories of day trips as a young boy, in Dad’s new car (a Jowett Javelin), speeding along the roads and seeing the beautiful Scottish countryside rushing by.

But pops always considered the square mile his “happy hunting ground”. Most of his chums, and almost all the people he met in a long career at Chubb, were there. As a result, he became one of the vast commuter army who, every morning, marched across London Bridge, on their way to work, in a dark overcoat, bowler hat, and carrying a rolled umbrella.

Like so many men of that era, Dad swapped his army uniform for that of a city gent, so he could build a better life for his wife and family.

“The land of milk and honey“

And then my brother died

My older brother “Richard” was what’s known as a “forceps delivery”. A manoeuvre carrying a much higher morbidity risk, even when performed by an obstetrician in a hospital. All the more so, when attempted by a midwife, in your bedroom.

That’s how it was back in the day, before the NHS had been invented (1948). For those who lived in, or near big cities, there were a few “county hospitals”. For the rest of us there were “cottage hospitals”, usually attached to doctor’s surgeries (which is how surgeries got that name, by the way). But, unless you were very posh, almost nobody went into hospital for childbirth, which is one reason infant death rates were so high. For most people the order of the day was a home delivery by the midwife.

However it happened, Richard didn’t survive. His tiny skull was crushed in delivery. In the end the doctors concluded mum’s diet had not included the necessary calcium forming foods, which had led to poor bone formation. Not uncommon in the post-war era where we still had food-rationing, and people were often malnourished.

The UK was the last country involved in the 2nd World War, to stop rationing food. It’s hard to believe, but rationing began in 1940, and didn’t end completely until 1954; nine years after the war ended.

The land of milk and honey was on its way, but clearly, it hadn’t arrived yet. But, I digress.

Mum was pregnant with me, but after the death of their firstborn, she was really apprehensive about childbirth at home. Dad pulled some strings, and when it was my time to come kicking and bawling into the world, I first saw the light of day in the Hillingdon County Hospital.

Ha ha! So, that was me, dead posh!

The following year my father was offered a promotion to Regional Manager: Scotland, Chubb Lock and Safe Co., so we all packed our bags, and off we went to live in Greenhill, North Lanarkshire, or Hareshaw village, as it’s now called; only ten miles from where I live today (2023).

Papa was running around Scotland in his new car, a Jowett Javelin, being “very important”, enjoying meeting the movers and shakers, and getting on with setting up his new Region. Mum, on the other hand, didn’t much care for Scotland; she was lonely and, for the very first time, away from her mum and dad, and her eight brothers and sisters.

The arrival of my wee sister “Susan” in March 1948 helped with the boredom a little, but she was keen to leave the village, Scotland too. She didn’t drive, the bus to town was once a week, and the village consisted of a doctor’s surgery, a village store and kids playground. And more boredom than one person needs.

Before we moved to Scotland, mum and dad didn’t have any time to go house-hunting together. The first time mum saw her new home was when the moving lorry rolled up at the door.

This led to three obvious questions — 1) Was the house the right house, in the right location? (clearly from mum’s perspective, it wasn’t). 2) Did its location make sense logistically, relative to dad’s job, and the customer base? 3) Was it located in the correct neighbourhood, with the right kind of schools, for an upwardly mobile executive, and his young family?

We’re batting zero for three, so far.

Now this is the kind of problem, if left unattended, can put the skids under the whole shooting-match. Poppa eventually realised he’d made a mistake with the house he’d chosen and delegated his new secretary to find something more suitable.

Apparently, he then came home with a proposal, one evening, discussed it with mum, and put it into action the very next day — cometh the day; cometh the man!

A new house in a posh part of Glasgow; “11 Hutchinson Drive, Bearsden” — bus routes, kindergartens, company wives, golf-clubs, neighbours, schools, kids parties, new house at the top of the hill, shops at the bottom — you get the picture. What’s not to like?

There was even a wee man who rode his bike up the street every evening (just as I was going to bed) and, with a long stick with an oil lamp on the end, lit all the gas lamps, and then came back in the morning, and snuffed them all out again.

Apparently, mum didn’t make friends easily, so she was still very lonely. She had no friends in Scotland, apart from a retired miner (Willie MacTavish) and his wife, who lived a few doors away at Greenhill, and had taken pity on her one day, as she pushed her shiny new pram around the village. And now she didn’t even have them to talk to.

In fact, she was so unhappy, dad asked George Chubb to transfer him back to London. The end result was that Scotland did not work out for either my mother or father, and my sister and I grew up in England, and lost our Scottish accents.

Sorry to end that story on a bit of a downer, but in real life, that’s often the way.

”I used to think you were just my dad”

~ Terence Milbourn

Leave a Reply